A Blunt Quotidian Exercise

Strauss Bourque-LaFrance, Stanley Edmondson, Miranda Fengyuan Zhang, Shio Kusaka, Calvin Marcus, Jorge Pardo & Lily Ramírez

May 6 – June 10, 2023

Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "The Snowing Sentence," 2023 Flashe, acrylic, collaged canvas, adhesives, artist frame 19 x 22 x 2 inches

Shio Kusaka "carved 105," 2016 Porcelain 6 x 5 1/4 x 5 1/4 inches

Shio Kusaka "stripe 103," 2013 Porcelain 10 x 5 1/2 x 5 1/4 inches

Calvin Marcus "Fish Lamp," 2023 Ceramic, bamboo, Japanese paper, glass bulb and wiring 21 1/4 x 12 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches

Jorge Pardo "Untitled (Merida House Lamp 02)," 2006 Plexiglas, lamp parts 24 x 22 x 20 inches

Jorge Pardo "Untitled (Red/Yellow Glass Lamp)," 2007 Glass, laser-cut MDF, lamp parts 16 1/2 x 20 x 12 1/2 inches

Jorge Pardo "Untitled (Blue/Yellow Glass Lamp)," 2007 Glass, laser-cut MDF, lamp parts 16 1/2 x 15 1/2 x 10 1/4 inches

Miranda Fengyuan Zhang "Ten Windows," 2023 Handwoven cotton 25 1/4 x 47 13/16 inches

Detail of Miranda Fengyuan Zhang "Ten Windows," 2023

Jorge Pardo "Wine Credenza," 2007 Walnut, painted plywood, electrical fan 18 x 23 x 93 inches

Jorge Pardo "Untitled (Set of 4 red lamps)," 2002 Plexiglass with light fixtures and electrical wiring 21 1/2 x 18 x 18 inches

Lily Ramírez "1998 TV," 2023 Acrylic on canvas 73 x 40 x 1 1/2 inches

Lily Ramírez "By the river," 2022 Acrylic on canvas 36 x 38 inches

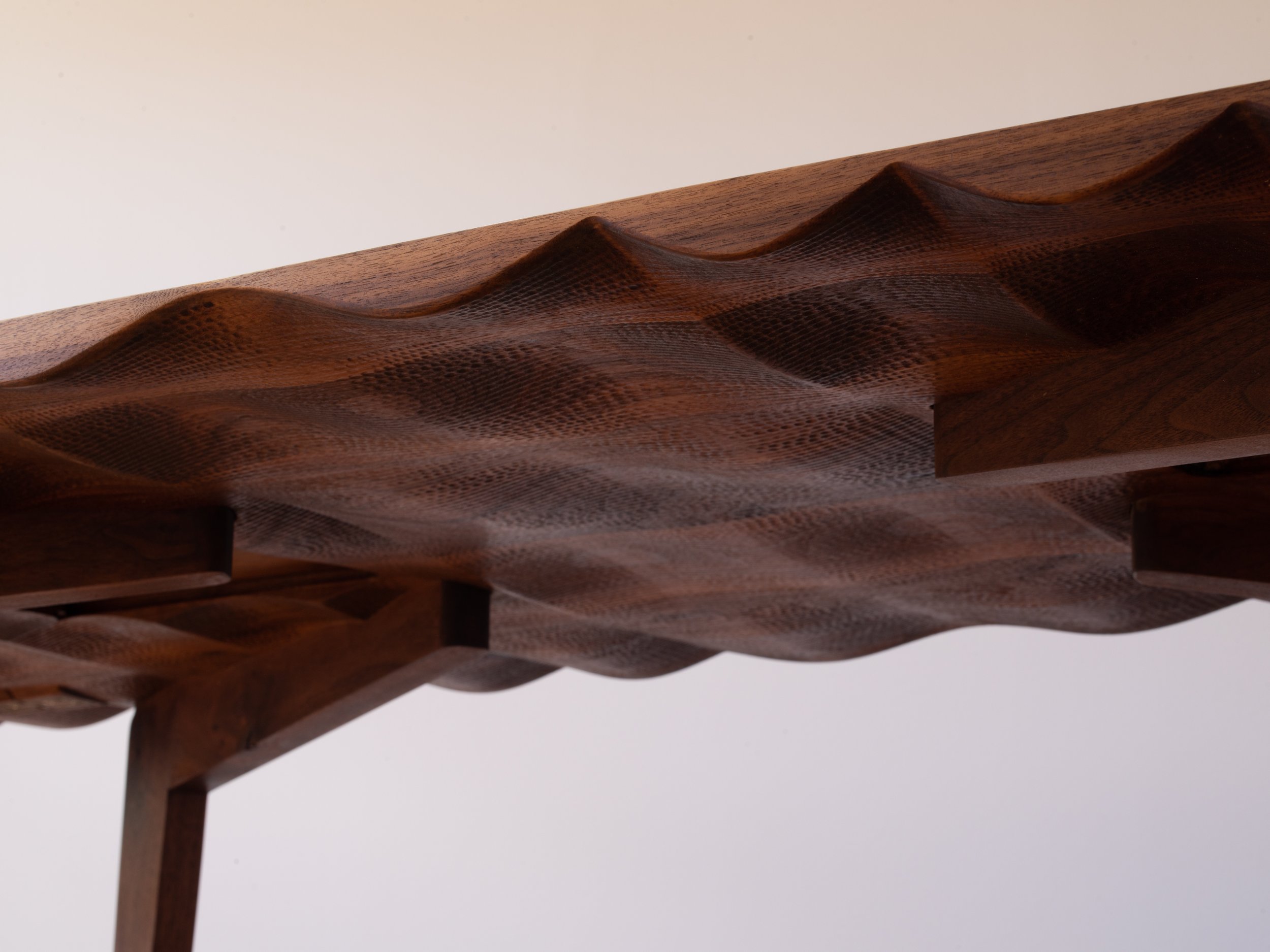

Jorge Pardo "Untitled (Dining Set)," 2004 Hand-carved table, table extensions, eight chairs in solid walnut 29 1/2 x 33 1/2 x 95 3/4 inches

Detail of Jorge Pardo "Untitled (Dining Set)," 2004

Jorge Pardo "Untitled (LACMA Pre-Columbian Room Lamps)," 2007 MDF, plexiglass, glass bulb, electrical parts 28 x 24 inches

Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Crying Composition," 2023 Flashe, acrylic, collaged canvas, adhesives, artist frame 22 x 19 x 2 inches

Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Roulette," 2023 Papier-mâché, resin 19 x 18 x 8 inches

Detail of Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Roulette," 2023

Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Trance," 2023 Papier-mâché, resin 19 x 18 x 8 inches

Detail of Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Trance," 2023

Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Rainbow Flame," 2023 Papier-mâché, resin 20 x 17 x 4 in ches

Detail of Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Rainbow Flame," 2023

Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Autumn Crown," 2023 Papier-mâché, resin 14 x 15 1/2 x 13 1/2 inches

Detail of Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Autumn Crown," 2023

Jorge Pardo "Untitled (Mountain Bar lamp)," 2009 Plexiglass with light fixtures and electrical wiring 24 x 24 x 24 inches

Miranda Fengyuan Zhang "Fences," 2022 and Stanley Edmondson "Flying Gigantor (Blue)," 2022 and "Gigantor Surfer (Blue Board)," 2023

Strauss Bourque-LaFrance "Earth Layer Song," 2023 Flashe, acrylic, collaged canvas, adhesives, artist frame 22 x 19 x 2 inches

Stanley Edmondson "Flying Gigantor (Blue)," 2022 Glazed ceramic

Stanley Edmondson "Gigantor Surfer (Blue Board)," 2023 Glazed ceramic 11 x 11 x 10.5 inches

Stanley Edmondson "Gigantor Surfer (Red & Yellow Board)," 2023 Glazed ceramic

Stanley Edmondson "Gigantor Surfers (Green Board)," 2022 Glazed ceramic

Stanley Edmondson "Foot Vessel (Blue)," 2023 and "Face Vessel (Rainbow)," 2023

“A museum comes up to an artist and says, ‘do you want to do a show?’ and you say, well I want to make a house. And I don’t want to make a house that goes in a museum, and I don’t want to make a house where something weird is going to happen, I want to just make a house and see what happens. It’s a very blunt quotidian exercise.“

–Jorge Pardo

A Blunt Quotidian Exercise, the third exhibition at Sea View, is a physical expression of the young gallery’s philosophy. This show is a display of the full expanse that Sea View has in store for its future programming — a multigenerational, interdisciplinary program that echoes the conception of its own architecture, 25 years ago.

At that time, Sea View was the studio & office of Jorge Pardo, an artist who has made a life’s work of exploding the functional and plastic arts. Here, he installed the building’s tessellated hardwood floors, its colorful bouquet of cabinets, and its precisely tiled bathroom. He also used the space as his own art studio and presented the entire home as a stand-alone artwork, on the occasion of his 1998 exhibition at MOCA.

With Sea View’s stewardship of the space, the gallery continues to reach for the kind of total work of art that Pardo had in mind. In A Blunt Quotidian Exercise, every element of the space is integral to the whole — the lamp in the corner by Calvin Marcus sits atop a countertop designed by Pardo; painted bowls by Strauss Bourque-LaFrance are served across the walnut dining table by Pardo; even the small ceramics by Stanley Edmondson scattered on the kitchen shelves are part of the ongoing “exhibition” and like almost everything else at Sea View, for sale. Here, art exists within, atop, below, and in direct relationship with other forms of art.

Like the space itself, A Blunt Quotidian Exercise is rooted in Pardo’s approach to art, where categories such as architecture, painting, design, craft, and installation are all activated simultaneously, without the fuss of delineation. Perhaps the piece that best expresses this approach is Pardo’s Wine Credenza (2007), in which a honeycombed rack stands behind elegant, folding doors. As is the gallery’s ethos, the credenza will be on display as a work and will also be put to work, stocked with the very wine served at the show’s opening. The piece will serve another purpose, as a surface — in this case, a plinth — for the porcelain vessels of Shio Kusaka. These works, and those by Bourque-LaFrance are also surfaces for painting and drawing, though each takes a significantly different approach to mark making. Where Kusaka’s lines are restrained and as soft as watercolor, Bourque LaFrance’s work seems to barely contain its exuberant colors, like expressionist painting in the form of dinnerware.

To make this relationship explicit, Bourque-LaFrance will exhibit two of his paintings that echo the mosaic-like compositions of his bowls, bringing the full gesture of painting (and its relationship to craft) onto the walls. Likewise, Miranda Fengyuan Zhang will display her fiber work on the walls. These are handwoven cotton tapestries, stretched like paintings, inspired by Johann Sebastian Bach and her grandmother’s practice of reweaving sweaters from recycled cloth.While Zhang’s fiber work recalls painting, Lily Ramírez’s paintings mimic the weaving of thick ribbons and plastic lace. Inspired by Robert Ryman, Ramírez builds up surfaces that are as sculptural as they are painterly, abstractions that appear as stitched as they are brushed.

Since little is taken for granted at Sea View, even the light for the show will come from the work itself, with Pardo’s Glass lamps (2005-2009) hanging above, like hovering hummingbirds, and a Calvin Marcus table lamp below. Marcus, a Los Angeles artist, is known mostly for his paintings, which usually contain a whiff of dark humor, and this lamp recalls the smirk of the California funk art movement; with its bamboo stem, casual lean, and the flopped fish that frequent his paintings.

Stanley Edmondson will also bring some funk humor to the show, with his ceramic planter, inconspicuous, outdoors and in shape of a giant foot. As with Pardo’s credenza, Edmondson’s Foot Planter will be put to use, housing flowering sage for the duration of the show. As the punny title suggests (“plantar” means “sole of the foot”), the pot will be literally the lowest piece in the show.

But to take the exhibition lower, blurring the boundaries of low & high culture, Edmondson evokes a little pop ephemera: toys and comics. His figurines draw upon 1960s Japanese graphic novels, especially the manga cartoon, Gigantor, and the collectable fetishes that such franchises produce. Like Kusaka’s porcelain vases, these robots will sit atop Pardo’s original cabinetry for the space, creating another of the show’s many unexpected collaborations across time and discipline.

Of course, setting a toy on a cabinet is no radical act; it’s as quotidian as it gets, really. Pardo has often spoken about his love of “ordinary things” and this show is a deep appreciation for the everyday ordinariness all around us. It begins with the most basic necessities of life: food, clothing, and shelter (holloware, weavings, and architecture) and then adds the things that we all add to our homes: furniture for the body, a flower pot for the yard, and perhaps, when we’re feeling audaciously impractical, a few paintings on the wall, for a little wonderful, useless joy.

–Ross Simonini