Independent 20th Century

Casa Cipriani

10 South St, NY

Booth D5

September 4-7, 2025

With Love, Bruce Richards

by Paul Maziar

For the artist Bruce Richards, painting is an act of trust—if not blind faith—in the power of the image and the process of its exchange with, and in relation to, his viewer. Reaching outward to the part of human nature that wills for understanding, Richards’s works refer to the symbolic resources of his lived experience. Over more than five decades, he's cultivated a body of work that transposes life’s twists-and-turns into objects of affection that, in their ambiguous dualism and talismanic potency, ring true across time.

A lifelong artist, Richards’s career began taking shape during his time at UC Irvine in the late 1960s. He studied under Robert Irwin whose indispensable influence would lead Richards to reimagine his raison d’être for creating work. After eventually earning a secondary teaching credential in 1971, Richards became an assistant for Vija Celmins and Craig Kauffman, from 1972-73, continuing a trajectory in art as both student and peer among artist-teachers of notable brilliance.

Art can change you, and at its best it changes with you. Richards knows this well. “Situations happen in ‘real time,’ which can repeat, reappear at any time, day to day” he says—and one is obliged to respond. His method evolved, leading to works that reflect equanimity, surprise, presence—with a visual poise that feels not familiar but rather, inevitable. Lit as if for the stage, his images have a presence, a psychic effect that they’ve always been there, waiting. Nine Richards paintings made between 1986 and 1996, on view at Sea View’s presentation at Independent 20th Century, invite the viewer into dreamlike vignettes with transcendent emblems that extend life and its ongoing negotiations.

Throughout Richards’s oeuvre, the dreamlike remains a consistent asset and in many of the works, he employs the aether in service to deeper, more diverse significance. Wind is a poet’s motif—the unseen force that brings moments of change and even humor, evoking ephemerality to point to the ineffable. It also can be seen as a metaphor for Eros, stirring the soul to beauty and transformation. Coitally-entwined chocolates, heart-topped weathervanes, fruit cascading in reverie or dialogue (apples-and-oranges in their classic diametrical opposition, colloquially speaking), operate at the edge of consciousness and hang around long after first encounters, loaded with tacit desire. Here, atmosphere is a metaphysical force charged with the pleasure of physical meaning-making. This imaginative transfer shows how art and the so-called real world exist side by side, starting with a vivid noun, a bit of vision. This is also an example of Richards’s situation of exchange as a leitmotif in this work, the negotiation of two sides.

In the late 1970s, Richards shifted away from the cool clarity of minimalism toward something more deeply rooted in lived experience. Richards’s early exposure to Irwin’s strictness of focus, his vast vision and, similarly, Celmins’s ethic—her meticulous observation and vision—helped him find his own focus. His painting would evolve beyond his influences to entail a process of discovery that fuses theoretical perception with the verity of the moment. The works would be set in inches not in feet, often within handmade frames—showing the artist’s own ethic of care.

“Current, lived events outweighed the focus on light and space,” he explains, recalling how he began to absorb his world and be absorbed by it, with a new means of articulating his vision. Living in downtown Los Angeles played a key role in this shift; the troubling realities outside his studio window demanding a new vernacular. In 1984, he met Kim Kanatani, who was on the education staff at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in Barnsdall Park, where he had a solo exhibition. The relationship marked a pivotal transformation and “a move from self-concern to concern for another.” Art became relational, not just expressive. It began to ask not “what is this?” but “who is this for?”

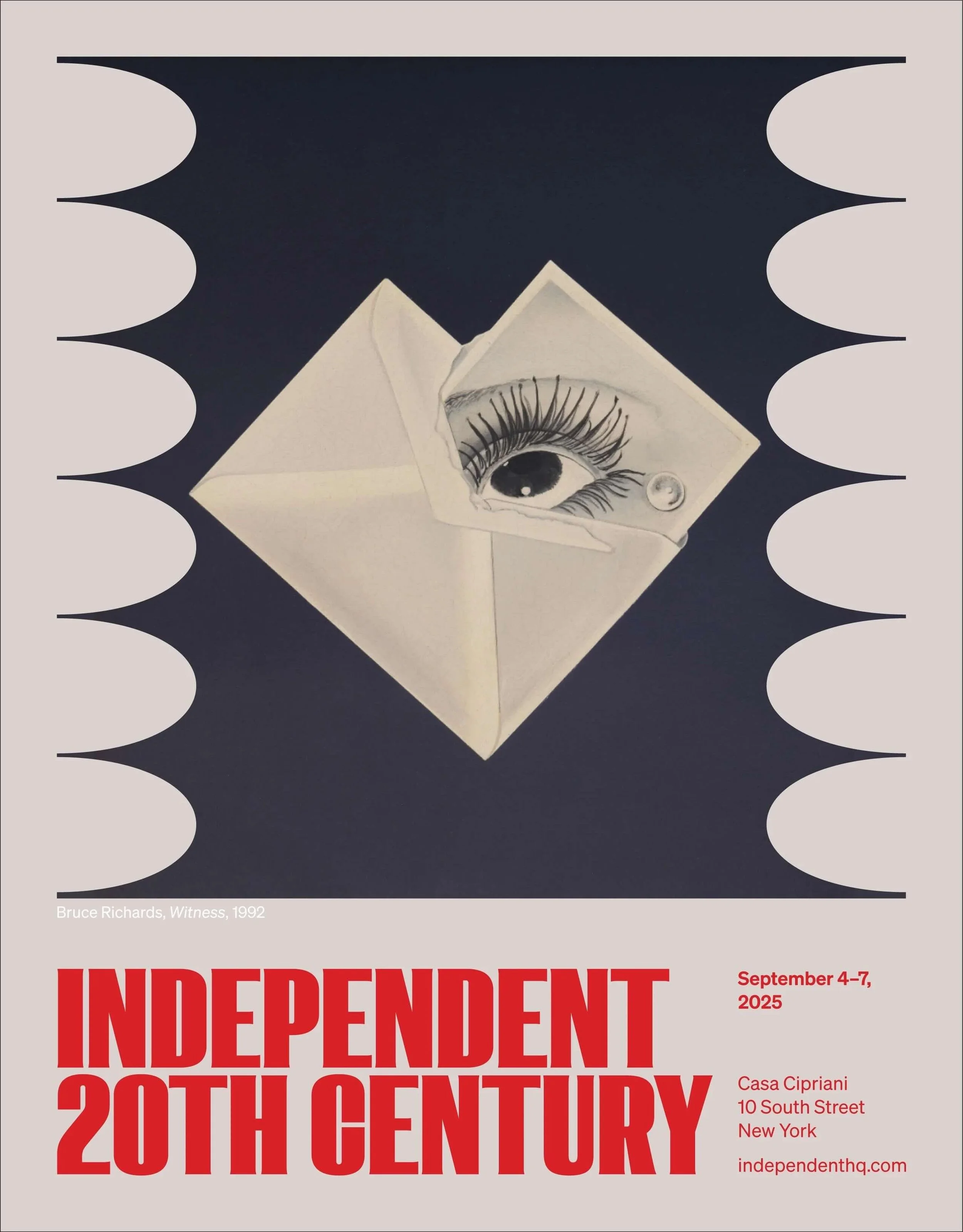

Speaking of dedication, Richards’s Love Letters began in 1987. The series highlights the artist’s ongoing interchange of ideas—a dialectic of choice by way of the museum gift shop postcard and envelope. The works include homages to Georgia O Keefe, Ed Ruscha, and Man Ray, documenting, among other things, Richards’s personal and relational considerations regarding direction—artistic and locational (relative to the American coasts)—love and death, commitment. They’re a nod to the various stages of courtship: early desire, falling in love, the witness of exchanged vows, and the commitment of marriage. Here, we might intuit the “‘leap of faith’ one needs to take to begin in a relationship when others give caution,” as Richards puts it. This series doesn’t illustrate love but rather, subtly proposes and tastefully discloses it.

If the Love Letters intimate the arc of romance, then the Change in the Weather paintings chart its strange currents. Two works from this period chart that sea-change, perhaps also foreshadowing Richards’s move from Los Angeles to New York. Yes (Gray), 1986 depicts a moment when emotional ambivalence gave way to determination: leaving behind one choice in favor of another. The tonal background’s shades of gray show differing values while, in the Change in the Weather series, gilt weathervanes reveal shifting emotional climates and changing luck in heart-shaped finials, lightning rods, directional heralds in varying faces. The hearts palpitate in and out of time, cajoling you to feel it all. “Climate change in life,” he comments. The wind shifts as life does. The cultivated culture of experimentation that celebrated the vernacular textures of California life shaped Richards indefinitely.

Throughout this body of work are what Richards calls “charged talismans” that take the heaviness and make it light. Often rendered in trompe-l’œil at 1:1 scale, the compositions flirt at the boundary of a particular place. No mere blandishments, they envelop the psyche. A letter and a rock (or cudgel, as haunting and heavy an image as any of them), a t-bone steak, an antique scissor—float suspended in a void, beset by the faint luminescence of some occult force. They’re not symbols to be decoded but presences to be reckoned with.

Richards’s lifelong practice is typified by sustained acts of attention, a devotion not just to his craft, but to his viewer’s experience. The work doesn’t present answers, but honors imagination, association, renewable states.

"Questionable (II)," 1990 Oil on canvas 21 1/4 x 16 in (54 x 41 cm)

"The New Breeze," 1989 Oil on canvas 59 3/4 x 36 1/2 in (152 x 92 cm)

"Change of Heart," 1989 Oil on canvas 58 1/2 x 36 in (149 x 91 cm)

"I Do," 1997 Oil on linen 18 x 14 3/4 in (46 x 38 cm)

"Icarus (Matisse 1947)," 1992 Oil on linen over panel 18 x 14 3/4 in (46 x 38 cm)

"Howl (II)," 1997 Oil on linen over panel 17 x 14 in (43 x 36 cm)

"Goodnight Moon (Brancusi 'Head of Sleeping Child' 1908)," 1990 Oil on linen over panel 18 x 14 3/4 in (46 x 38 cm)

"Spring Heart V (My Heart to You)," 1999 Oil on linen 6 3/4 x 7 3/4 in

"Spring Heart IV (My Heart to You)," Oil on linen 6 3/4 x 7 3/4 in

"Witness," 1992 Oil on linen 17 3/4 x 14 5/8 in (45 x 37 cm)

"The Request," 1982 Acrylic wash on paper 21 x 20 in (53 x 51 cm)

"Yes (Gray)," 1986 Oil on canvas 55 1/4 x 30 1/4 in (137 x 74 cm)

"Delilah," 1981 Watercolor and oil on paper 28 x 25 in (72 x 64 cm)